In a previous blog, I made the (possibly) bold claim that least-developed countries like Angola can learn from the success of developed countries like Norway.

While poor countries can look to near-peers for development models, they should pay close attention to aspirational peers for a long-term vision of development success. But how in the world can a postcolonial African country replicate the success of a once-colonial European country in 2024?

Today, I want to explore in more detail how, despite their differences, Angola can learn from — and potentially replicate — Norway’s success.

What Norway did right

Since 1967, Norway has relied on a government pension fund to subsidize national insurance. In 1990, the Government Pension Fund Global was founded specifically to invest surplus revenues from Norway’s petroleum sector.

Today, Norway’s “Oil Fund” holds over 1.6 trillion USD in assets and is the largest sovereign wealth fund in the world. In the first half of 2024, the fund earned 138 billion in profits (Norway’s GDP in 2023 was 485 billion).

Unlike so many developing countries, Norway consistently invests national resource profits into a wealth fund — which then reinvests its returns into the national and global economy. The returns on these investments subsidize Norway’s government expenditure, including its generous social safety net.

It cannot be overstated how much this approach insulates domestic programs from market fluctuations. By not only committing natural resource profits to government programs, but first investing those profits into national funds, Norway’s successive governments have been able to fund one of the happiest societies in the world.

Angola’s turn

Angolan has never enjoyed the decades of deep government investment Norweigians have. But every country has to start somewhere.

In 2008, President José Eduardo dos Santos began a process that would culminate in a new sovereign wealth fund, the Fundo Soberano de Angola. Officially formed in 2012 (45 years after Norway’s), the FSDEA today holds just over 2 billion USD in total assets (Angola’s GDP in 2023 was 116 billion).

Overall, this is precisely the kind of move that I advocate for, and I’m not alone. The World Economic Forum finds that “sovereign wealth funds are playing an increasingly important role in global development,” representing 11.3 trillion dollars in assets.

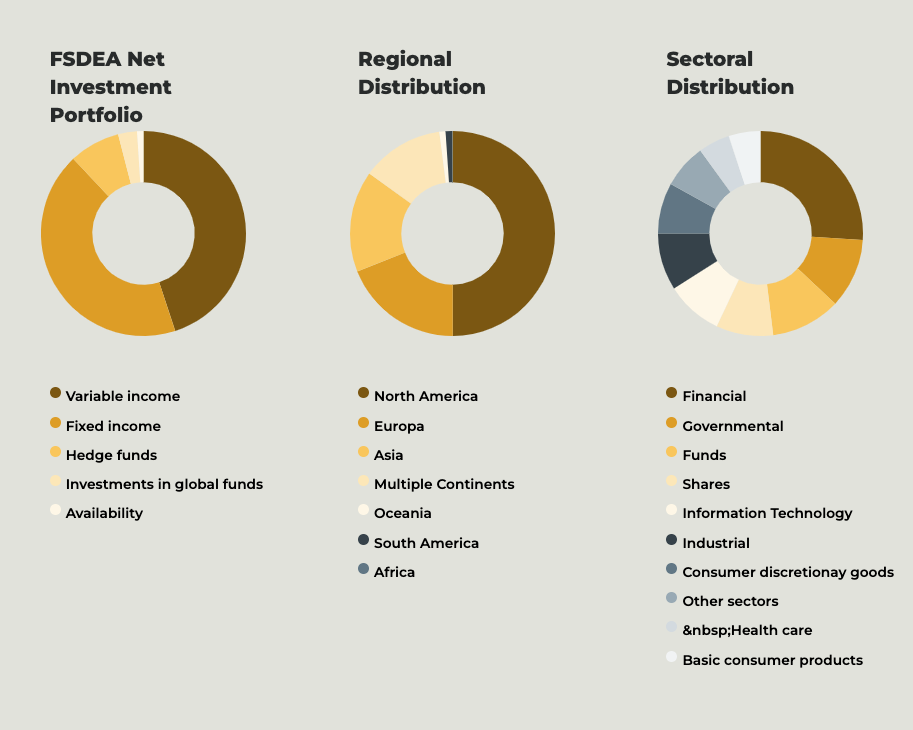

Angola has started to invest its resource revenues in the global market to build the kind of sovereign wealth that can support its citizens’ long-term prosperity. As a member of the International Forum of Sovereign Wealth Funds, Angola follows the Santiago Principles which provide guidance on accountability and good governance. The FSDEA’s holdings are diverse across sectors, regions, and types of income.

Of course, we can’t ignore the giant gap between the size of Angola and Norway’s funds. Or that Norway’s GDP is spread across a much smaller population than Angola’s.

Ultimately, we can’t compare postcolonial states with wealthy European nations without addressing the elephant in the room: debt.

From sovereign debt to sovereign wealth

For decades (and not always by choice), poor countries have had to spend, borrow, and spend some more in the hopes of jump-starting their economies. Over the long term, this has led to the debt crisis plaguing the Global South.

For poor countries that happen to be resource-rich, compounding debts and deficits can make SWFs seem like overly ambitious long-term approaches.

Instead, governments have to squander new revenues to meet short-term needs. When the alternative is mass starvation, it’s no real alternative at all.

So, our initial question evolves: How do poor countries develop sovereign wealth while navigating high debts and small tax bases?

For the last few years, Angola has done well to follow the multifaceted strategies that built the wealth of wealthy nations.

In 2024 (for example), Angola’s National Institute of Support to Micro-, Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (INAPEM) partnered with UN Trade and Development to create a plan that enhances local entrepreneurship. Moves like this resonate with efforts in Norway to support SMEs facing inflationary pressures today.

The Angolan government’s work isn’t stopping there. Sonangol, Angola’s national oil company, is also expanding production as they move toward partial, then full privatization in a bid to increase foreign investment.

From a development standpoint, we can clearly recognize how government support for both SMEs and major industries can transform a national economy. We should appreciate this multi-pronged approach.

Still, just this year, Angola borrowed an additional 400 million dollars from the World Bank to fund its Kwenda program, a cash-transfer initiative for its poorest citizens.

With Angola’s 2025 budget forecast showing a growing deficit, the country is reportedly in talks for another financing program with the IMF.

Takeaways

Angola’s efforts to build and develop their sovereign wealth fund reflects opportunity-based economic development in action.

Angola’s sovereign wealth fund represents an opportunity-turning factor, leveraging revenues to grow a fund which can support government expenditures in the future.

For the FSDEA to achieve its purpose, Angola’s successive governments must address the factors supporting these opportunities (like increased oil production) and the factors resisting opportunity (like sovereign debt).

This means learning both from near-peers like Kenya and aspirational peers like Norway. And, while the potential lessons are endless, here’s what stands out to me.

First: Borrowed funds must be invested strategically, and ultimately paid back, for the national economy to grow sustainably.

Angola’s investments in the Kwenda program won’t be fully realized unless support for the poorest Angolans translates to increased labor participation. The success of Angola’s social programs is just as important as its ability to grow the FSDEA.

Angola can’t fall into the same trap as Haiti, Kenya, and so many others — growing the national debt to support programs that don’t translate into greater economic participation.

Second: Fluctuating annual revenues based on a global commodities market cannot form the basis of a stable, long-term budget.

The catastrophe in Venezuela should make this clear. Directly subsidizing national expenditure with resource profits leaves every government program at the risk of price shocks.

This makes the success of a national fund crucial, especially as oil producing countries navigate the energy transitions which will have massive repercussions.

Third: every fund needs time to grow, and every withdrawal extends that time frame.

For this reason, it might actually make more sense for Angola to borrow to cover short-term budget shortfalls — especially if interest rates on these loans are lower than the fund’s rate of return. We should be careful not to ignore the near-term context in which Angola is trying to foster long-term growth.

Lastly: development is about happiness.

The people of Angola, Norway, and everywhere else are just looking for an opportunity to create their own success. Neither rising GDP nor a growing wealth fund can fully speak to the effectiveness of a development approach. These are mechanisms, not outcomes.

Opportunity-based economic development means looking beyond simple metrics and focusing on the outcomes we want to achieve. Unless we assess development in a holistic way, we can easily confuse increased production with actual improvement.

Unfortunately, Angola has yet to appear in the World Happiness Report. Like many developing nations, poverty means not being represented in the data. And we simply cannot address an issue if we can’t see it.

So, even as we laud Angola’s efforts to develop a sovereign wealth fund, even as we celebrate how it’s learning from its peers, let’s also advocate for more holistic assessments to ensure we’re capturing the full story.

I look forward to the day when Angolans are counted among the happiest people in the world.