my articles

What does President Trump’s second term mean for developing countries?

Last month, Donald Trump won nearly 77 million votes to secure his second term as president of the United States. The Republican party will control the House and Senate, and three of his appointees sit on the Supreme Court.

In many ways, the world is going to experience the full extent of President Trump’s vision for the first time, free of prior constraints. While his critics raise concerns about his zero-tolerance immigration policy, and a potential rise in federal deficits, President Trump’s supporters tout his plans to reduce government waste, strengthen energy independence, and create new jobs.

Ultimately, President Trump’s “America first” vision is going to have major implications for the developing world. I believe his policies are going to create significant opportunities, especially for the nations poised to take advantage of new openings in existing supply chains.

Leaders in developing countries will need to navigate these implications as we continue pursuing economic growth, human development, and the betterment of humankind.

What does “America first” mean for the world?

Since his first term, Donald Trump has espoused an “America first” perspective. This position aims to bring jobs back to the US, especially in manufacturing industries.

In reality, Trump’s vision is part of a broader trend, sometimes called deglobalization. Though international trade remains intense, and will continue to grow, developed countries are trying to restructure supply relationships with middle-income and developing countries.

Since President Trump’s first term, international trade patterns have shifted as segments of different supply chains relocate to overcome emerging barriers. For example, China is now only the US’s fourth largest trading partner, with total trade valued at $575 billion in 2023, while Mexico ranks first, with total trade valued at $789 billion in the same year. (It’s crucial to remember that Joe Biden largely kept Trump’s tariff structure in place, even adding new tariffs on Chinese goods in May of this year).

So, what does Trump’s second term mean for developing countries — and how can we leverage these changes to create opportunity and accelerate growth?

New opportunities amid accelerating protectionism

All in all, President Trump’s “America first” vision means greater protectionism — which mostly comes down to higher tariffs on US imports.

In 2016, Trump’s administration began to renegotiate the US’s position in the global order, pulling the US from the Trans-Pacific Partnership in 2017. While Joe Biden joined the new Indo-Pacific Economic Framework in 2022, Trump has already vowed to withdraw. He also signaled a potential withdrawal from the World Trade Organization.

Interestingly enough, while Biden reversed a US exit from the WTO during his term, his administration has left its court of adjudication empty. This rendered the WTO incapable of enforcing its rules. I take this as another sign of the bipartisan support for renegotiating the US’s position, in spite of partisan criticisms.

So what does all of this mean?

For the next four years — and probably for several more after that — we will see increased barriers for global firms doing business with US industries and consumers.

New barriers might slow the development and integration of supply chains around the Pacific (representing some 40 percent of global trade). And, Trump’s threats to put tariffs on the BRICS nations are on another level. As Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa, and some other nations have discussed dropping the US dollar for international trade, Trump has promised 100 percent tariffs on any goods these nations export to the US.

There’s a lot of concern and fear about what the future holds, but we should pay more attention to emerging opportunities.

For my part, I see tariffs as an instrument to balance trade, if used in measured and strategic ways. As US trade with the world has helped to enrich all parties, the US middle class has borne the brunt of globalization’s impacts on employment. Every US leader, democrat or republican, has to protect domestic labor opportunities. Really, this goes for every nation in the world — developed or developing.

Typically, I oppose most government policies that might reduce trade or increase them in unhealthy ways. Tariffs are risky tools because they always come with two dimensions: the tariffs you impose and any retaliatory tariffs from trading partners. That’s why they should be a mechanism of last resort.

I view President Trump’s tariff policies as a gamble. It may be risky, but he’s ultimately betting on American firms.

For example, new tariffs on goods entering the United States might increase consumer prices in the short term, but that creates the opportunity for price competition. President Trump is betting that American companies will find new partnerships which are more advantageous to the US workforce.

After all, consumer demand in North America remains strong. While inflation remains a serious concern, Americans are still shopping this holiday season. Developing countries with emerging manufacturing sectors will have a greater opportunity to attract investment and step up production as price competition intensifies.

In fact, Indian commentators are already speculating about the new opportunities increased US tariffs on China may create. We already know that Apple is actively diversifying its manufacturing, shifting a significant portion of iPhone production from China to India.

While it’s not great for some Chinese manufacturers, firms in developing countries are poised to take advantage of a new competitive price advantage and grow exports to the US.

Manufacturers in Mexico, India, and other countries were the ultimate winners of the US-China trade disputes under Trump and Biden. Over the next few years, I expect more winners to emerge among developing and even some least-developed countries.

Now is the time for foreign direct investment in developing-world firms that can manufacture the goods which will be impacted by new US tariffs.

Accelerating instability in the global supporting environment

If only we only had to concern ourselves with trade.

National policies are ultimately the turning factors that can move economies forward. However, a supporting environment is key to turning demand into opportunity (something I’ve discussed at length in my books).

Armed conflicts could be the decisive variables that impact Trump’s policy vision. Developing countries that want to take advantage of new opportunities could find themselves constrained by variables they can’t control.

For example, Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, and simmering tensions with NATO, could spell further disaster for the region. In the Middle East, escalations in Iran, Israel, Lebanon, and/or Syria could inflame the region — which is possible regardless of US intervention.

All of this could spell increased demand for humanitarian aid, even as Trump has promised further cuts to US aid spending, including a withdrawal from the World Health Organization. While this might mean more suffering in the short-term, my hope is that aid efforts are redirected toward the kind of trade that can actually create wealth, rather than just maintaining misery.

In terms of climate action, President Trump might withdraw the US from both the Paris Agreement and the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. That said, leaders in California, Texas, and elsewhere have signaled that renewable energies are key areas for job creation. As AI and crypto drive more and more energy demand, investment in clean energy is only going to grow.

Furthermore, adjacent industries, from semiconductors and high-tech products to pharmaceuticals, are being impacted by the current China shock. These developments point to new opportunities for partnerships between the US and developing countries.

Finally, while Trump’s mass deportation plan is often understood in domestic terms, I think we should consider the international implications. For nations like Haiti, Guatemala, and others, the systematic deportation of migrants back to these countries will strain already limited capacities — and I hope to explore this issue more in a future post.

Regardless of US immigration policy, the flow of migration north throughout Latin America seems likely to continue as more and more people are displaced by conflict or environmental destruction. As the US stems the flow of migrants entering its southern border, migrants will continue to collect in Central American countries.

Migration to this region has had largely negative consequences, but it also presents an opportunity: A growing regional labor force. Latin and Central American governments that assimilate regional migrants into their labor forces could grow their tax bases, helping to pay for social services.

What now?

I hope this article gives you a clear and fair picture of how the next four years of US foreign policy might impact the developing world.

While US policy could exacerbate global crises, it also has the potential to bring peace and prosperity to the globe.

In the past, the US has been an exceptional partner to some nations and a significant barrier for others. I remain optimistic that Trump’s second term can create new opportunities for trade, partnership, and growth.

However, let’s make one thing clear before we go: The leaders of the developing world are ultimately responsible for ending poverty and creating opportunity in the developing world.

My hope is that we can navigate these challenges and opportunities together.

References

“Election 2024.” Associated Press. 2024.

“U.S.-China Trade Relations.” Congressional Research Service. 9 December 2024.

“U.S.-Mexico Trade Relations.” Congressional Research Service. 6 June 2024.

“Retailers Say Shoppers Are Pressured, Stretched, and Cautious.” Bsuiness Insider. 6 December 2024.

“Will India gain as Trump points tariff bazooka at China?” India Today. 26 November 2024.

“India’s iPhone hopes and South Korea’s EV concerns.” Financial Times. 29 August 2024.

What can Angola learn from Norway? The role of sovereign funds

In a previous blog, I made the (possibly) bold claim that least-developed countries like Angola can learn from the success of developed countries like Norway.

While poor countries can look to near-peers for development models, they should pay close attention to aspirational peers for a long-term vision of development success. But how in the world can a postcolonial African country replicate the success of a once-colonial European country in 2024?

Today, I want to explore in more detail how, despite their differences, Angola can learn from — and potentially replicate — Norway’s success.

What Norway did right

Since 1967, Norway has relied on a government pension fund to subsidize national insurance. In 1990, the Government Pension Fund Global was founded specifically to invest surplus revenues from Norway’s petroleum sector.

Today, Norway’s “Oil Fund” holds over 1.6 trillion USD in assets and is the largest sovereign wealth fund in the world. In the first half of 2024, the fund earned 138 billion in profits (Norway’s GDP in 2023 was 485 billion).

Unlike so many developing countries, Norway consistently invests national resource profits into a wealth fund — which then reinvests its returns into the national and global economy. The returns on these investments subsidize Norway’s government expenditure, including its generous social safety net.

It cannot be overstated how much this approach insulates domestic programs from market fluctuations. By not only committing natural resource profits to government programs, but first investing those profits into national funds, Norway’s successive governments have been able to fund one of the happiest societies in the world.

Angola’s turn

Angolan has never enjoyed the decades of deep government investment Norweigians have. But every country has to start somewhere.

In 2008, President José Eduardo dos Santos began a process that would culminate in a new sovereign wealth fund, the Fundo Soberano de Angola. Officially formed in 2012 (45 years after Norway’s), the FSDEA today holds just over 2 billion USD in total assets (Angola’s GDP in 2023 was 116 billion).

Overall, this is precisely the kind of move that I advocate for, and I’m not alone. The World Economic Forum finds that “sovereign wealth funds are playing an increasingly important role in global development,” representing 11.3 trillion dollars in assets.

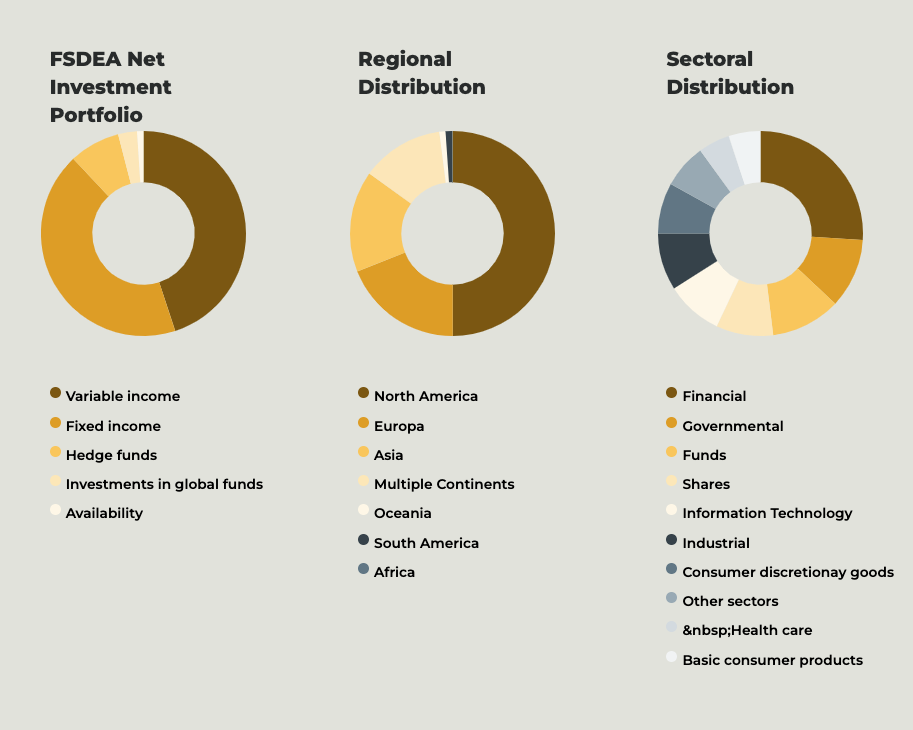

Angola has started to invest its resource revenues in the global market to build the kind of sovereign wealth that can support its citizens’ long-term prosperity. As a member of the International Forum of Sovereign Wealth Funds, Angola follows the Santiago Principles which provide guidance on accountability and good governance. The FSDEA’s holdings are diverse across sectors, regions, and types of income.

Of course, we can’t ignore the giant gap between the size of Angola and Norway’s funds. Or that Norway’s GDP is spread across a much smaller population than Angola’s.

Ultimately, we can’t compare postcolonial states with wealthy European nations without addressing the elephant in the room: debt.

From sovereign debt to sovereign wealth

For decades (and not always by choice), poor countries have had to spend, borrow, and spend some more in the hopes of jump-starting their economies. Over the long term, this has led to the debt crisis plaguing the Global South.

For poor countries that happen to be resource-rich, compounding debts and deficits can make SWFs seem like overly ambitious long-term approaches.

Instead, governments have to squander new revenues to meet short-term needs. When the alternative is mass starvation, it’s no real alternative at all.

So, our initial question evolves: How do poor countries develop sovereign wealth while navigating high debts and small tax bases?

For the last few years, Angola has done well to follow the multifaceted strategies that built the wealth of wealthy nations.

In 2024 (for example), Angola’s National Institute of Support to Micro-, Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (INAPEM) partnered with UN Trade and Development to create a plan that enhances local entrepreneurship. Moves like this resonate with efforts in Norway to support SMEs facing inflationary pressures today.

The Angolan government’s work isn’t stopping there. Sonangol, Angola’s national oil company, is also expanding production as they move toward partial, then full privatization in a bid to increase foreign investment.

From a development standpoint, we can clearly recognize how government support for both SMEs and major industries can transform a national economy. We should appreciate this multi-pronged approach.

Still, just this year, Angola borrowed an additional 400 million dollars from the World Bank to fund its Kwenda program, a cash-transfer initiative for its poorest citizens.

With Angola’s 2025 budget forecast showing a growing deficit, the country is reportedly in talks for another financing program with the IMF.

Takeaways

Angola’s efforts to build and develop their sovereign wealth fund reflects opportunity-based economic development in action.

Angola’s sovereign wealth fund represents an opportunity-turning factor, leveraging revenues to grow a fund which can support government expenditures in the future.

For the FSDEA to achieve its purpose, Angola’s successive governments must address the factors supporting these opportunities (like increased oil production) and the factors resisting opportunity (like sovereign debt).

This means learning both from near-peers like Kenya and aspirational peers like Norway. And, while the potential lessons are endless, here’s what stands out to me.

First: Borrowed funds must be invested strategically, and ultimately paid back, for the national economy to grow sustainably.

Angola’s investments in the Kwenda program won’t be fully realized unless support for the poorest Angolans translates to increased labor participation. The success of Angola’s social programs is just as important as its ability to grow the FSDEA.

Angola can’t fall into the same trap as Haiti, Kenya, and so many others — growing the national debt to support programs that don’t translate into greater economic participation.

Second: Fluctuating annual revenues based on a global commodities market cannot form the basis of a stable, long-term budget.

The catastrophe in Venezuela should make this clear. Directly subsidizing national expenditure with resource profits leaves every government program at the risk of price shocks.

This makes the success of a national fund crucial, especially as oil producing countries navigate the energy transitions which will have massive repercussions.

Third: every fund needs time to grow, and every withdrawal extends that time frame.

For this reason, it might actually make more sense for Angola to borrow to cover short-term budget shortfalls — especially if interest rates on these loans are lower than the fund’s rate of return. We should be careful not to ignore the near-term context in which Angola is trying to foster long-term growth.

Lastly: development is about happiness.

The people of Angola, Norway, and everywhere else are just looking for an opportunity to create their own success. Neither rising GDP nor a growing wealth fund can fully speak to the effectiveness of a development approach. These are mechanisms, not outcomes.

Opportunity-based economic development means looking beyond simple metrics and focusing on the outcomes we want to achieve. Unless we assess development in a holistic way, we can easily confuse increased production with actual improvement.

Unfortunately, Angola has yet to appear in the World Happiness Report. Like many developing nations, poverty means not being represented in the data. And we simply cannot address an issue if we can’t see it.

So, even as we laud Angola’s efforts to develop a sovereign wealth fund, even as we celebrate how it’s learning from its peers, let’s also advocate for more holistic assessments to ensure we’re capturing the full story.

I look forward to the day when Angolans are counted among the happiest people in the world.

Norway as a lesson for developing nations

Norway is one of the happiest countries in the world, with a per capita GDP of over 100,000USD.

Nordea Bank predicts “better times ahead for both the Norwegian economy and the housing market,” in spite of global challenges like inflation.

So, what does Norway have to do with my work? What does any of this have to do with developing economies?

Development professionals are encouraged to look to “near peer” nations for solutions—and I will always champion that approach.

We can also look for “aspirational peers,” countries whose success we want to replicate, even if we’re not there yet.

Looking at the Norwegian economy, it’s easy to identify key reasons for their success: natural resources and a long history of investments in education and social services.

“Norway is now the largest energy provider to Europe and ranks as the 4th largest exporter of natural gas globally,” according to the US ITA. Norway’s merchant shipping fleet is also one of the largest and most modern in the world.

It should be clear that countries like Haiti and the Democratic Republic of Congo have a radically different history with radically different factors impacting potential growth.

Still, Norway’s example demonstrates a few key takeaways that leaders in developing nations need to internalize. In fact, it’s a perfect example of how national governments can apply the principles of OBED, opportunity-based economic development.

First: Norway proves that a strategy of reinvesting revenues from natural resources into social services works. Norway’s success demonstrates why Angola is moving in the right direction (as I wrote about in an earlier post).

Norway was able to transform its natural resources into new marketable opportunities by first investing those profits, then reinvesting any returns into social services. Doing so leveraged the country’s comparative advantages to foster an opportunity-generating economic environment.

A second key takeaway: Long-term investments in education and social services are necessary to create an active, vibrant labor force that generates growth both through productivity and consumer spending.

The OECD snapshot for Norway shows an economy that navigated the pandemic better than many other countries. It seems reasonable to attribute some of this success to a well-funded network of hospitals, daycares, hospices, and other institutions that had the resources to respond to the emergency.

Reducing deaths and illnesses from the disease meant that Norwegians got back to work sooner. That success is reflected in its faster post-pandemic growth compared to other OECD countries. All of these successes can be understood as the logical outcome of a sustainable growth strategy.

Countries like DRC might look to Angola, but countries like Angola can look to Norway—and other high-income countries—to understand how to adapt their strategies going forward. This is especially important as living standards and formal labor force participation improve.

Success stories like Norway provide a clear path to optimizing opportunity, and they can help us avoid certain pitfalls.

Notice that Norway didn’t just sell its oil and invest those returns directly into social services. By first investing in the market, those revenues could support other industries, helping to diversify the economy and protect against cyclical fluctuations in commodity prices. Maximizing these revenues through investment then optimized Norway’s public expenditures.

This is how a country optimizes its economic opportunities. Norway didn’t choose between public investments and public services. They leveraged one strategy against the other to achieve an optimal return.

The next time you’re working on a vicious problem in a developing economy, look to near-peers for solutions, but don’t forget to consider what aspirational peers are doing as well.

Remember a key OBED principle: opportunities must always lead to new opportunities. It’s a “both-and” mindset, not just “either-or.”

Let’s not just try to help developing countries escape poverty.

Let’s help developing nations grow wealth, and happiness, using proven models for success.

Why has Haiti collapsed? Blame monopolies.

In July, thousands of Haitians in the US and around the world protested the violence in our motherland. After months of begging for an intervention, a Kenyan-led UN security mission is in works.

Like many Haitians reading these stories, I wonder: What good is a security solution that doesn’t address the economic roots of the crisis?

Haiti’s real problem is explained in one word: monopoly.

A tiny part of the population controls key industries, killing opportunities for millions of Haitians. No serious account of Haiti’s political and social problems can ignore the near-total consolidation of economic power.

Take the steel industry, controlled entirely by one family: the Bigios. They control Aciérie D’Haiti, and all of the steel operations in Haiti. A few other families control imports of rice, cooking oil, and other key goods and sectors. When every entrepreneurial avenue is closed off by monopolies, how can the average Haitian make a decent living?

I was born in ’79, toward the end of the father-son Duvalier regime, which ruled from 1957-1986. In my 44 years, I’ve known vanishingly few Haitians to have found normal jobs or entrepreneurial success in Haiti. If you can’t escape to the US (which entails its own challenges), the options are limited to this: selling cheap exports in the informal economy, working brutal hours in a sweatshop, eking out a meager subsistence on a tiny farm, or death.

Nearly 40 years since the Duvalier regime’s fall—through four decades of coup d’etats and other crises—Haiti is worse off than ever.

The effects of monopoly are severe and compounding. First, the incentive to maintain monopoly leads to anti-competitive practices. Rather than investing in worker’s skills or other kinds of innovations, monopolies look to lower costs, raise prices, and further exploit their market position. (US readers need only consider their internet service providers for a reminder of how monopolies impact consumers).

Without competition, there’s little room, or incentive, for collaboration. Industry partnerships that might enhance the capacity of other firms become risks rather than synergies. Without energetic competition and collaboration, we see an erosion of pluralistic institutions (think industry associations or chambers of commerce). Without these institutions, it becomes impossible to coordinate and diversify investment, foster innovation, and optimize economic output at the national level.

Of course, no monopoly goes unchallenged. The more they exploit workers and consumers, the more they encounter resistance. This is why monopolies need political corruption (if not over dictatorship) to survive.

The US State Department has recognized the links between Haiti’s political and business elites and the armed gangs. Just a few weeks ago, the Canadian government sanctioned Gilbert Bigio (of Aciérie D’Haiti) and several other businessmen accused of supporting the gangs.

This is good news, but a few sanctions (and even a security mission) won’t cure what ails us.

Over 200 years of Haitian history, economic monopoly has been a constant. But this was never inevitable. Other nations recognized and responded to the threat of monopolies, from the Dutch West India Company, to Bell Atlantic, to Meta.

In 1915, the US Congress established the Federal Trade Commission, creating an institution with an explicit mandate to curb monopoly power. Today, the European Commission antitrust inquiries into Microsoft and other tech companies show a clear commitment to competition.

While the international community debates Haiti’s future, let’s make one thing absolutely clear: Monopolies have always been a driving cause of Haiti’s problems; they were never just a symptom.

If we’re serious about meaningful change in Haiti, any further international interventions needs to squarely target Haiti’s monopolies.

My next blog posts will go into detail about potential solutions. For now, here are four things that Haitians and the international community can do:

- Ensure that the UN-approved mission to Haiti eliminates the gangs and prosecutes their leaders and financiers. Any security intervention must have a specific, time-bound mandate, limited to reinforcing the National Police. Anything else will only repeat the foreign invasions of the past.

- Hold elections and elect a government with a clear mandate to support and enhance the judiciary. An operational legal structure is fundamental to curbing monopoly power.

- Create a legal body, similar to the US FTC, that outright forbids economic monopolies. This body must carefully regulate industries to protect workers and maintain competition.

- Reform the tax code to encourage entrepreneurship. Our 200-year old tax code is inadequate to curb the power of monopolies.

Each of these steps is extremely difficult. Success is never assured. But other countries have curbed monopoly power and established a competitive economy.

We can do the same.

Technology and Innovation in Haiti: Recognizing the Challenges and Taking Advantage of the Opportunity

Technology and innovation in Haiti offer a plethora of opportunities for growth for Haiti, the small-island nation state in the Caribbean. When one hears the word innovation, the first thought might be of Uber, patents, big-budget R&D departments, and/or creating cool, new products that makes people’s lives easier. However, OECD (2005) gives a comprehensive take on what we actually mean by innovation. “Innovation is the implementation of a new or significantly improved product (good or service), or process, a new marketing method, or a new organizational method in business practices, workplace organization, or external relations.” (46). It is important to think about innovation in all of these contexts as you move through this piece.

First, there are obviously challenges when it comes to the implementation of technology and innovative activity in Haiti, a country with poor economic indicators across-the-board, poor infrastructure, weak institutions, and instability, which can make it an uphill battle to realizing these opportunities of growth. The speed of adoption or the ability to even adopt a technological change or innovative activity of large scale is something that is more prevalent in developing countries. Again, weak institutions and infrastructure, and sub-par distribution channels that would be the vessels for relaying and quickly adopting technological change or adaptation cause this problem. There are also usually high costs when trying to prove proof of concept and in the first few years of the life span of the innovation or technology, especially when considering implementing or introducing a new product. So, in Haiti, where the distribution channels are weak, marketing isn’t as influential of a tool, and a large percent of household budgets are going towards basic needs, having something catch on can be a difficult task.

Another challenge is that there is large incentive to operate under the table for employers, mostly because of the lack of over sightor ability for the government to monitor informal market activity. The gig economy is alive and well (moto drivers for transportation, construction workers, odd jobs, and the presence of self-employment and bartering informally is something that results in lost tax revenues for the government, which would give the government a larger pool to draw from when investing in things like infrastructure, education, or healthcare. Whether it would get spent there is another question. However, the point is, people want to keep their money, and if they can work informally without much threat, they will.

The opportunities for Haiti to establish itself as a magnet of investment, innovation, and technological change are there, and there are many positive actions that can be taken right now that will allow technological change and innovation to spur greater levels of economic growth.

First, one can look at how foreign direct investment has historically impacted economic growth and development. Huet et al. (2015)analyzes the impact of what a new mobile phone operator did for Haiti in terms of development and economic growth. After a 260 million dollar (USD) investment between the years 2005-2009, Digicel created a ripple in the economy in terms of jobs, tax revenue, and overall growth (181). Digicel’s investment led to 63,000 direct and indirect jobs being created, and at the time of writing, Digicel had contributed to around 20% of Haiti’s GDP growth. When taking into consideration the three mobile phone operators in Haiti, they represented between 25-30% of tax revenues in 2011. It’s beyond the scope of this piece to lay out the many ways that foreign direct investment has positively impacted economic growth, job creation, and tax revenue. But, this is just one example of the impact that foreign direct investment can have in these areas. Ultimately,economic growth is what we aim to maximize in development and job creation and tax revenue are obviously beneficial as well.

Another one of the opportunities is that if you teach,empower, and foster entrepreneurial people, those internal characteristics built can overcome barriers in a place like Haiti. Individuals with this pedigree can enter the labor market, can climb corporate ladders or start businesses, and make decisions that will have a positive impact, because of who they are and what they’ve been taught.

This leads to the next point, that there are things that can be done right now that can allow technology and innovation to be a conduit to greater levels of economic growth in the near future. NGOs, schools, and other institutions should start training for STEM-type jobs right now. There is an argument that is sometimes made that lower-income countries aren’t as susceptible to tech changes that are going to modify what the labor market looks like because the labor force and the economy don’t yet have the capability to receive it successfully. But, I would argue that it will happen quicker than a largely agrarian and gig economy might expect, and that it will just skip steps (and large revolutionary shifts) in the labor market, leaving more people behind.

If you build it, they will come.

As a nation, Haiti should not only seek to incentive investment and new technology both from foreign firms and domestic but should be proactive in readying its labor force and its leaders of tomorrow to be able to capitalize on high-skill jobs that will come. It is important for the federal government to realize that they play the most crucial role in proactively and indirectly triggering investments into the nation, investments that will propel the economy and the nation forward. Fostering camaraderie between the powers at be and the people and attempting to create an environment where people want to put their money is a great first step in attracting investments with technological and innovative characteristics. It is also important for teacher sand organizations to realize that they play a role in this too. They should seek to provide opportunities outside the scope of normal education based on test scores and regurgitated information. STEM curriculum, gifted programs to challenge high-IQ children, economics or debate clubs, and chess are all ways to begin to be ready when the technology and innovation comes.

Click here to read my book ‘ From Aid to Trade’ for more analysis of how Haiti and other developing countries can get out of poverty.

References

Huet, J., Viennois, I., Labarthe, P., & El Barkani, A. (2012). Impact study of the arrival of a new

mobile phone operator in haiti.Communications & Strategies, (86), 175-192,219-

221,223.

OECD/Eurostat (2005), Oslo Manual: Guidelines for Collecting and Interpreting Innovation

Data, 3rd Edition, The Measurement of Scientific and Technological Activities, OECD

Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264013100-en.

Women entrepreneurship: A Sure Path Forward for Haiti’s Economy

History books in Haiti and all over the world will forever bear pages of the events of the January 12th, 2010 earthquake that changed how the world looked at Haiti and her people.

Almost a decade later, Haiti is still a stark difference to what the media has fed the world. We’ve heard that the aid agencies significantly reduced health challenges, starvation, poverty and every different situation the country faced at the time.

Not Quite

But as much as the media paints the wonderful and succesful strides Haiti has taken ever since that dreadful event that shook our very core; I want everyone to know that Haiti remains a shadow of what it was once with even a more grim possibility to climb out of it.

Some might argue the country is gradually rising from the rubble of the catastrophic event that crippled our economy. What have we been able to show for it? On the opposite, the constant economic decline begs to differ.

Foreign Assistance

For several decades, Haiti has lived on foreign assistance in the form of grants and our economy would’ve thrived if we hadn’t allowed these grants to get in way over our heads. I have discussed on several platforms that foreign aids aren’t what a third world country like Haiti needs. It is merely a short-term solution, while the real problem of economic instability, low GDP, entrepreneurial crisis and dependency pervade.

So, how we get our economies back up and running in no time? How do we move our economy from what it is now to where we all want it to be?

After a careful evaluation of our problems as a nation, and what other nations are doing to become developed countries, I have laid out ways our own country: One of many I would like to discuss is Women Empowerment through entrepreneurship.

Subsistent Farming

It is no longer news that most of the people who engage in subsistent farming and micro businesses are women. They are also the ones who invariably bear the pain of catering for their immediate families. Unfortunately, women in Haiti are mostly succumbed to mostly minor roles and do not get involved enough in leadership. Obtaining the necessary funds to improve what they are doing can be a challenging task.

We are faced with a dilemma. After the earthquake happened, a significant number of women retreated to take responsibilities back in their homes, and the socio-political sphere of our country was left with a male-dominated atmosphere. With only one woman in the senate in Haiti today, women are and still are being segregated in Haiti. For our economy to truly move beyond the aid narrative, and for us to truly have an economic boost, it’s a known fact that women are natural leaders, so let’s involve them in policy making roles, politics, in small and medium scale enterprises so they can contribute towards short and long-term economic recovery of Haiti.

Their acumen and deftness in handling crisis is what Haiti needs. So, let us encourage and empower our women. After all, the first fair elections that have happened in Haiti were done under a woman’s leadership. We should trust and encourage more of that to happen.

Investing in skills training

Another ingredient to help our economy grow is investing in our skill acquisitions and entrepreneurship development programs. Unemployment has been a Haitian problem long before the devastating events of the earthquake. It has increased exponentially in 8 years.

We have a pressing need right now. We want to curb dependency on foreign aids and support, and we can achieve this through investing in labor-intensive products, manufacturing, textile industry and agriculture. If our government can invest in our youth in skill and entrepreneurship development initiatives, the fight to be more dependent to focus better on driving our economy to lofty heights will become more evident.

Foreign Investment

Entrepreneurship creates the avenue for foreigners to invest in our industries, expanding the businesses which pave the way for job creation and improve the unemployment index. When foreign countries invest in our industries, instead of providing tied-end grants, we will begin to experience economic change with better numbers on the GDP, and national income.

We must also note that through entrepreneurship, more people are getting involved and jobs are created, a tax can be generated to boost the internal revenue board. The funds generated from these taxes can be used to focus on sectors like the construction industry, the healthcare sector, the transport sector, the energy sector, and most importantly the tourism sector.

Entrepreneurship development can bring about more innovative and faster ways to do labour, which can increase productivity and generate more GDP and increase exports out of the country. Income from exports that will help our economy grow.

China and Japan

Look at China and Japan. These countries have been rocked over the years by earthquakes and tsunamis. But they were able to look past the rubble and focus on improving their economies. They saw the disasters as an opportunity to do better, and today both countries are the largest exporters of technology in the world.

Haiti responded differently. We saw foreign aids as our beacon of hope, instead of foreign investment in our agriculture and many other industries. We drove our local entrepreneurs out of business because the competition from the foreign agencies that intervened was fierce and they couldn’t keep up.

But like China and Japan, we can do the same, and we can even do more to revive our economy better than it was before the disaster. We have before us an opportunity to sieve through the history books yet again in the near future. We have before us a window of opportunity to engage in reforming towards prosperity so others can say If Haiti, after all these many years of remaining stagnant can raise up and boast of a good economy, we can too.

A Reflection on Haiti’s Economy in 2018: A Snapshot

As we turn the page to a new year and we struggle to remember to turn our 8s into 9s, it is important to look back at what happened in Haiti in 2018. There was some good, some bad, and some lessons to be learned economically and politically that we can use to change Haiti into a place that is business-friendly and a champion of growth moving forward. In my book, From Aid to Trade, and in past pieces, I have explored why it is important to attract investment, how we move from aid to trade, and why this growth that I talk about that comes from it is important for Haiti’s future.

I will start by laying out some economic indicators and data that encapsulates Haiti’s economic situation in 2018 and then move toward my thoughts on some of the events that happened in 2018.

Summary of Economic Indicators

Below is a chart showing the trade deficit trend from January 2018 – August 2018 (latest data available).

[iframe src=’https://d3fy651gv2fhd3.cloudfront.net/embed/?s=haiaitibalrade&v=201811211633a1&d1=20180101&d2=20191231&h=300&w=600′ height=’300′ width=’600′ frameborder=’0′ scrolling=’no’]

Below is a chart showing a trend of Haiti’s Exports from January 2018 – September 2018 (latest data available).

[iframe src=’https://d3fy651gv2fhd3.cloudfront.net/embed/?s=haiaitiexpxports&v=201811211630a1&d1=20180101&d2=20191231&h=300&w=600′ height=’300′ width=’600′ frameborder=’0′ scrolling=’no’]

Below is a chart showing a trend of Haiti’s Imports from January 2018 – August 2018 (latest data available).

[iframe src=’https://d3fy651gv2fhd3.cloudfront.net/embed/?s=haiaitiimpmports&v=201811211631a1&d1=20180101&d2=20191231&h=300&w=600′ height=’300′ width=’600′ frameborder=’0′ scrolling=’no’]

By looking at the following chart it is clear that Haiti lags drastically behind the rest of the world when it comes to attracting foreign direct investment, and although data for 2018 is not yet available, the disparity and trend is clear in comparison with developing economies, other individual countries, the region, and the world.

The unemployment rate in 2017 was 13.99%, according to the World Bank. Because it is difficult to capture dense data in Haiti and with the prevalence of informal workers, this number can be taken with a grain of salt.

In 2018, the currency was devalued in relation to the dollar. All this means is that we purchasing power became weaker… we went from seeing $1 USD equal around 64 gourdes (in January) to around 77 gourdes at the close of the year. Inflation was at a whopping 13.27%.

Inflation is simply the natural rise of prices in an economy and decrease in the value of purchasing power. Talk to anyone… things like rice, vegetables, chicken, rent, transportation etc… became more expensive, and it hurt the people. Here you can look at the changes in price for staple items in different regions of Haiti for both domestic and imported goods.

As we see in the charts, Haiti is running a severe trade deficit—we are importing more than we are exporting—and this has negative long-term implications for employment, economic growth, and the value of the gourde.

The Events That Tell the Story of 2018

Economic indicators can tell a small part of the story for a country, but I think that a few major events encapsulate the state of Haiti’s economy in 2018. Talking about them helps us to understand the implications it has for our country. The infamous July fuel price hike, which occurred after a mandated subsidy-lift on fuel, caused instability in a period that was a prime time for tourists and visitors to come down and spend their dollars in the economy. This measure was necessary for the Haitian government to obtain 96 million dollars (USD) from the European Union, Inter-American Development Bank, and the World Bank.

You could say that the intentions were good from the IMF for its subsidy-lift which could lead you to saying that the Haitian government was simply trying to uphold its end of the bargain. You could also say that the uprising from the Haitian people was justified because of what happened to commodity prices, price and supply of gasoline, and subsequently the livelihoods of families across the nation when the price hike went into effect.

I think another lowlight of 2018 and a clue that corruption is still alive and well was the issue of the Petrocaribe money. This refers to the $2.8 billion in low-interest dollars that has been given to Haiti since 2008 from Petrocaribe, a Venezuelan-led oil-purchasing alliance. “Kot Kòb Petwo Karibe a?” became a battle cry for the people of Haiti in our attempt to fight against the corruption that has been a common occurrence in Haiti. Where did the Petrocaribe money go? It is suspected that it went to ghost businesses and the political elites’ pockets, along with other financial misuses. I think that the people deserve to know what exactly happened, and the parties need to be held accountable. I am not speaking against corruption because I am trying to be politically manipulative or because I disagree with someone’s politics. I just know that corruption is going to be the thing that holds Haiti back from achieving what I know we can achieve as a country. Whether an internal commission or foreign independent body unravels the details of if the money actually went to government officials’ pockets and shady businesses remains to be seen. Hopefully the persistence and mostly non-violent demonstrating by the Haitian people will lead to bringing to light what exactly has happened in this case of corruption.

The Impact of Unrest

How has Petrocaribe impacted the economy? On September 19th, 2018, my firm, Bridge Capital, organized the first National Day of Foreign Investment in Haiti. At this event, our goal was to connect entrepreneurs in Haiti to a group of American investors. Not only was this an opportunity to network and collaborate under a shared vision with the Haitian government, institutions, investors, and citizens, but there was the potential for dollars to be pledged to good business ideas, which in turn would create jobs, lead to higher productivity, and positively impact the economy. This was the inaugural event of a push and mindset shift that Haiti desperately needed.

Entrepreneurs and businesses that are poised for growth exist in Haiti, and there are institutions like Bridge Capital and foreign investors looking to try and make an impact and create value through entrepreneurs and ideas they believe in, in a country where it is needed. All in all, a total of 2.4 million dollars (USD) was pledged to businesses that had pitched their ideas that day. In my previous posts, I looked at How Haiti Can Create Wealth and Enjoy a More Prosperous Future and How Haiti can be More Open for Business: Building a More Attractive Business Climate and outlined how and why foreign direct investment and an attractive business climate will benefit Haiti as it has many other countries around the world. Check them out to gain a more wholesome understanding on why something like this is so important.

Added to the lost of investment is the opportunity cost for businesses losing much needed revenue to curb inflation and grow to create employment, taxes and overall economic growth. Businesses in lodging, transportation, food and beverages as well as entertainment lost significant amount of income during the days of unrest as well as near and long term opportunities from cancelled purchase orders, guests and travellers to Haiti. Can Haiti further afford such lost?

Unfortunately, as you may have seen, in late 2018, we had to differ all monies pledged from the Foreign Direct Investment Forum, an amount which totaled 2.4 million dollars (USD) which included capital allocations to four businesses, due to political instability and elevated risks. Ultimately, this was a tough decision because of the impact we know that investments like these can have when a political and economic climate allows it to be a vessel for growth and success. So, the Petrocaribe scandal and the tension from the fuel price hikes caused instability, which kept away investment dollars that otherwise would have been helping reversed the escalading depreciation of the gourde and a positive impact for Haiti’s economy.

Looking backward but focusing forward

One of the positives coming out of 2018 is the growth potential for textiles. From January to November the number of workers in the textile sector increased from 48,820 to 52,950. Several foreign countries have invested in Haiti in textile facilities, but the lack of the Haitian state’s support has caused the plans to not come to fruition. There was an investment by Palm Apparel Group in the amount of $15 million, but this investment echoed Bridge Capital’s decision to pull pledged dollars. It never went through because of the socio-political situations that festered in 2018. I believe that you can learn how to handle the future by looking at the past. It is time for us to strengthen our institutions and come together to get rid of the corruption that is keeping investments like these out of the country.

As I look back on what happened in 2018, continuing to speak out for truth and for justice is one of the most important things I can do. I will also continue to speak out informatively about how the good and the bad actions of policymakers, institutions, and the people affect economic growth, job creation, and the livelihoods of the people in the nation that I love. When we start to understand the economics of things like halted foreign direct investment, government corruption, political instability, and a devaluation of the currency, all of which we saw unfold this year, we can begin to make better decisions about how we approach these situations and what types of scars they can leave on a country. 2018 was a year where GDP growth in Haiti gained .50 % but was below expectations and was one of the lowest growth rates in the Caribbean and Latin American regions. However, it was also a year in which we learn from 2018 and we turn the page. Looking forward, forecasted GDP growth is expected to jump to 2.4% in 2019 and grow again at 2.4% in 2020, according to the World Bank. Such miraculous growth in wealth creation would be a much needed answer to prayer!

As post-natural disaster influxes of human and physical capital start having some breathing room to take shape, 2019 could be a year where change happens. People are fed up, and the government is in the spotlight. The young people try to leave to find employment in Brazil and Chile but are being sent back by the thousands. As I continue to work to educate and inform you on the many intricacies of development and economic policy in Haiti and how change is going to come for the better, I hope everyone will look to what I say with an open mind and with a confidence that 2019 is a year where we change how the world sees Haiti and how we see ourselves. In 2020, when we look back on what happened in 2019, I hope that we will see change, even if it is slow to come to fruition.

Haiti’s economy is behaving like a business that is consistently ignoring its consumer preferences and end up of offering a product or service no one wants, completely out of synch and unhinged with reality. Business like this goes bankrupt. That means, most of the sectors that are competitive and are creating jobs and move double digit growth around the world are not even being considered by Haiti’s leadership. Let alone put in place the stability and policies needed for more businesses to pursue more opportunities to enlarge the size of the economy and create more wealth.

Today, when the manufacturing of capital good, tech related products, capital markets and services industries are creating massive wealth, Haiti settles for consumer goods and low margins products like t- shirts and agricultural production (when that’s even there) with zero presence of a real financial market to capitalize one while exporting good most of the time within their natural state. It’s an economy with less than minimal leverage and that’s a sign of extreme lack of productivity. Ultimately, Haiti’s economy is not performing to the level that will move its citizens out of poverty. The growth rate is simply too insignificant. The road for Haiti is bright considering the opportunities but the challenges are equally significant which means the country is stagnant. The only way forward is through better leadership and a drastic change of direction for the economy.

Be watching for a blog on why strong institutions matter (as discussed briefly here) in the fight for strong economic growth and a stable business environment.

Click here to read my book ‘ From Aid to Trade’ for more analysis of how Haiti and other developing countries can get out of poverty.

References

http://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/global-economic-prospects#data

https://www.miamiherald.com/news/nation-world/world/americas/haiti/article214497129.html

https://unctad.org/sections/dite_dir/docs/wir2018/wir18_fs_ht_en.pdf

https://www.nytimes.com/svc/oembed/html/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.nytimes.com%2F2018%2F12%2F26%2Fopinion%2Fhaiti-corruption.html#?secret=oMWHZN4xnq

https://www.statista.com/statistics/575624/inflation-rate-in-haiti/

https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Haiti_2018_09_PB_EN.pdf

Why Reliable Government Institutions Matter in the Fight for Robust Economic Growth

In a recent post, I discussed how Haiti can create wealth and enjoy a more prosperous future. I touched on why economic growth and creating wealth is the primary goal of economists and policymakers and how Haiti can create economic growth. It is not really a point of contention that economic growth and wealth creation isn’t good or that it isn’t important for Haiti. As I’ve talked about economic growth and the future success of Haiti, one of the things I have mentioned is the importance of strong institutions. In this piece, I want to help you better understand what institutions are, the evidence of why strong institutions are arguably the most important factor for low-income countries in being able to break the cycle of poverty, how we quantify or define a strong institution, and how Haiti can get there. Creating strong institutions sounds like a fluffy, wide-ranging concept that people at places like the World Bank talk about as being key to prosperity. However, at the end of this piece, I hope you will gain a better understand about what strong institutions are and why they matter.

An institution can be defined as an “establishment, foundation, or organization created to pursue a particular type of endeavor”. You could also define institution as a “mechanism of social order”. Think of an institution as the “foundation”, the “environment”, or the “glue” that holds a country and an economy together. Institutions are a plenty. Businesses, non-governmental organizations, the legal system, the police force, a central bank, the office of the presidency, etc. are all institutions. Yes, a single individual in an office is an institution. In this piece, we are highlighting the role of government institutions in Haiti’s growth more specifically.

Evidence of the Importance of Institutions

There is a lot of evidence from studies, both theoretical and empirical, that show the importance of why strong institutions matter in the fight for strong economic growth. I won’t get into the intricacies of the studies or the empirics behind them, but I will share some of the findings.

Dort, Meon, and Sekkat (2013) found that investment increases economic growth more in countries with high institutional quality than in countries with defective institutions. The results are driven and measured by metrics like government instability, corruption, and rule of law.

Das and Quirk (2016) also found that institutions matter in term of economic growth, but different institutions matter differently for growth. They concluded that poor countries benefit the most from market-creating institutions and institutions that support market stability, like a central bank, for example. They also conclude that democratic institutions are not necessarily optimal for growth in poor countries. So, you can see that financial stability and institutions that create a perceived strength and stability are important for poor countries. With the devaluation of the gourde, inflation, and the overall instability, it is plausible to say that these are big drivers of Haiti’s inability to attract investment and create economic growth right now.

Furthermore, goal 16 of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals is titled Peace, Justice, Strong Institutions. Did you know that among the institutions most affected by corruption are the judiciary and the police? Is this true of Haiti? Can weaknesses in these institutions help explain why Haiti doesn’t have robust economic growth? This is one of the Sustainable Development Goals because strong institutions create trust between a government and the people, a central bank and investors, and a judicial system and a police force, for example. The interconnected web of relationships in Haiti that need to be stronger, more trusted, and more equitable is a long list. Strong institutions also help bring together the “haves” and the “have-nots”.

Thinking about weak institutions in the real world

So, how do you quantify or define a strong institution? Think about it… if people engage in bribery or don’t get prosecuted for their crimes because there is corruption in the justice system, what discourages future crimes? If a government employee takes aid money and keeps it for himself or funnels it where it doesn’t need to be, the people don’t see the benefits and international aid bodies will consider wrongdoing like that in the future. Using the World Bank’s Doing Business Report of 2019 that just came out, Haiti has come out as the worst ranked country in the world in terms of investor protection. If there is no trust (if the institutions involved in investment aren’t strong) why would anyone want to invest… and we know how important investment is.

Property rights ensure ownership, the ability to legally and transparently buy and sell the asset in a market, and insulation from corrupt officials or criminals. This is important for economic growth and for a strong economy. But, legitimate property titles are often non-existent in Haiti, and even if they do exist, they conflict with other records or titles for the same property. It can also take months or longer to even verify titles. These are all examples of weak institutions, and Haiti has a lot of them.

How Does Haiti Strengthen Its Institutions?

I have laid out some evidence from economists and have given some practical examples of what weak institutions look like in the real world. How does Haiti get to a place where its institutions are strong, and how long will it take? I have four suggestions or steps that can be taken that will lead us to having stronger institutions. One is to have people of credibility in institutions. This won’t happen overnight, but it starts with educating our young people, speaking against injustice, speaking up for truth, and training the leaders of tomorrow to have integrity, step up to the challenge, and be confident to work towards position of power or influence. The second thing that needs to happen is for the public to be informed. We saw an example of that with the Petrocaribe scandal. What started out as a hashtag quickly spread like wildfire and took Haiti by storm. Today’s interconnectedness online and ability to share information will make this the most easily attainable. It is already happening, and transparency further discourages bad behavior. The third suggestion for Haiti is to encourage peaceful, but contestable elections, while the fourth and final suggestion is applicable to the international community. Institutions in Haiti need oversight and accountability. The institutions themselves (the central bank, government, judicial system, committees, etc.) need to humble themselves and welcome it. This would create a stronger Haiti.

There are of course direct effects of stronger property rights, a fair justice system, a police force that works for the badge and the force, and institutions in general that are fair and do the right thing. But, there would be additional effects of having stronger institutions. Creating stronger institutions would lead to more dense data for economists and policymakers and would allow oversight and policymaking to be flexible and Haiti-specific; dense, up-to-date data is hard to come by. Strong institutions create trust. Strong institutions can happen in Haiti, which will in turn matter in the fight for strong economic growth, but as for how quickly it can happen, there is no exact answer. I can say that Haiti does not carry the same burden as more resource-rich countries in sub-Saharan Africa. These countries have historically faced an uphill battle in combatting weak institutions because resource-rich countries have built in conflict, something of value, and an incentive to fight for de facto political power.

Government ensures policies are applied. They are crucial to implement rules, regulations that foster economic transformation. Countries with weak institutions are likely to lag behind and dwell in practices that breed more poverty than wealth. Having reliable and working institutions can simply mean being poor or wealthy. Just simple as that. In the end, I think that this is one of the more looked-over policy focuses when it comes to creating growth because it isn’t necessarily an exciting policy topic. However, that doesn’t make it any less important.

Click here to read my book ‘ From Aid to Trade’ for more analysis of how Haiti and other developing countries can get out of poverty.

References

https://www.export.gov/article?id=Haiti-Protection-of-Property-Rights

Why Haiti creates more poverty than wealth today. The reason: we are myopic.

In my last article, ‘The end of Haiti’s problem is not for tomorrow’, I explained how Haitians are poor today. It was very easy to explain because Haitians gave birth to 152,210 babies in 2018 at the same time the growth of GDP in nominal terms was $126 million. 1.5% GDP growth vs 1.31% the population growth. Doing the math, basically, the average Haitian is netting a deficiency of $3.30 a day, thus causing them to live in poverty by a greater amount than they have to meet their needs. This is where we are as of March 4th, 2019.

But, for cry out loud, how did we get here?

Almost unrreal but Haiti has found ways to squander its best opportunities over time: the ability to learn, apply and grow. Nations of the world have learned and applied what they learned and generate substantial growth resulting in better living conditions for their citizens. Haiti has not. Rather, it has gone down the path of self-destruction as the prioritized method of solving problem with no chance of learning to do things better, a double sadness.

Haiti’s past opportunities

After its independence, which was gained from destroying plantations and killing the colonists, it was expected to completely liberate the slaves and allow for economic reforms prioritizing large property farming in agriculture to sustain the key position in the world’s most lucrative markets at the time in agricultural products such as coffee, cocoa etc. That would have been the right and the best thing to do. We did no such thing; instead we divided the country into smaller plots and allow each and every one to plant tiny farms allowing an agriculture of subsistence to take place and grow overtime. The agricultural sector became weak over time while other nations gained substantial ground.

After the industrial revolution, nations of the world have been taking advantage of machines to allow productivity to take place, building factories, equipment to help building infrastructure like road, bridges

and facilities for health, schools. Overtime, mechanization has removed most workers from agriculture but, instead, put them in factories to allow more jobs to be created while increasing the productivity in both sectors. We did no such thing. We leave most of country men and women working with pick axes and hoes with virtually no trace of substantial manufacturing.

Now, when hundred people are needed to farm here, a few workers, one tractor and some equipment are needed to yield far more results elsewhere leaving an untapped opportunity to create jobs in both agriculture and the manufacturing of that tractor and equipment with advanced knowledge and technology. That is exponential growth for countries that embrace this type of opportunities and they are economically and socially better for it. This is called economic progress, unfortunately only visible in other countries.

Post industrial revolution, production techniques and accumulation of knowledge allow for goods to be created easily with less resources which triggered the needs for marketing, customer services, insurance, banking etc… basically the creation of a whole service sector. The transition and growth from working bare farms to factory integrations have triggered many opportunities for employment and economic growth for the countries that had the vision to upscale in that direction. That would have been the coolest and most productive thing to do. Haiti does no such thing. Instead, did the same old thing. The thing that doesn’t work. The unproductive thing. Haiti has continued the sad path of poverty creation leaving its citizens lingering in abject poverty.

Haiti’s present situation

The basic order at a restaurant today will testify of how far behind we are in the service sector and how customer service is none of our concerns. We act like we don’t care while the rest of the world is moving forward and most of us live in dire poverty but yet, we fail to realize today the poverty is directly related and connected to our inability to adapt and pursue the right opportunities that were presented in the past and present. This is called myopia. Myopia in medical terms is when you don’t see far. In economic development terms, myopia is the inability to foresee future opportunities and remain stuck in the present. That explains why we still prefer leaving

most of our country men and women working the field with bare hands with no sights of manufacturing and almost no integration in the service sectors; all perfect opportunities to create employment and create wealth.

Haiti’s future

I had the opportunity to interview recently a gentleman named Freud Dimitry St Louis, the CEO of Haiti Job Booster. Freud is in his early thirties and believes in Haiti’s future. He thinks Haiti still has a shot at becoming self-sustaining but has to catch up on over two hundred years of capital accumulation by building an economic consensus to integrate what the world needs the most with what we do best. This is what I describe as our angle of opportunity. While Freud gave no further thought to this, it brings me to my own economic framework developed in my first book ‘From Aid to Trade’ of how opportunity can become a trigger for economic growth.

What service jobs has to do with it

The word today needs services, visual content and faster processes. What if Haiti, this time, does not let this opportunity lags behind but instead embraces it and train hundreds of thousands of young men and women in IT, transcript, customer services and allow young Haitians to bypass the mechanization in agriculture, factory but skip directly into serving countries customer services, HR while sitting at home enjoying the warm climate. With a higher income, we would be able to buy more from the local market and that would trigger economic growth from within. That’s what India is doing and many other countries are taking advantage of this opportunity to create massive employment for their youth. We can do this thing. It’s not too late.

My friend, Fednar Duquesne, along with Digicel and many other companies are doing just that today. It just has to be expanded and become a worthwhile industry to be developed with the right tax incentive, capital and government support. Having a dream for Haiti’s development include anticipate on sectors in high demand and propose proactive solution instead of missing or ignoring those opportunities and write about it with regret fifty years from now. We need to do this. We can do this.

Click here to read my book ‘ From Aid to Trade’ for more analysis of how Haiti and other developing countries can get out of poverty.